Just when I’d begun to hope that egregious appropriation of indigenous cultural productions was beginning to decline, new cases are making headlines. Nearly as troubling as the persistence of such acts of injustice is the viral spread of the “cultural appropriation” meme and its invocation in situations that flirt with triviality, a trend that risks undermining the term’s moral force.

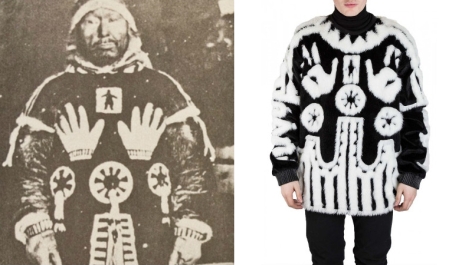

In late November 2015, a UK fashion house was called out for selling very expensive sweaters that featured a design copied from a the parka of a long-dead Inuit shaman from Nunavut. The shaman’s descendants complained, the story hit the media in the US, Canada, and elsewhere, and the company withdrew the product from sale after issuing a rather tepid apology. Why a publicity-attuned corporation would think that their design theft would go unnoticed in a digitally interconnected world is anyone’s guess.

A more complicated case involves a group of Boy Scouts from southern Colorado who since 1950 have been performing Native dances that they identify as originating in the Hopi Tribe of Arizona, arguably one of the Indian nations that has most energetically defended its traditional religious knowledge and practices. There is little question that the “Koshare Indian Dancers,” as the dance troupe is called, began as a romantic act of homage to Native Americans. Over the years, the group has performed across the United States in highly publicized and celebrated events. The director of the Hopi Office of Cultural Preservation, Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, has recently protested the performances, which Hopis regard as culturally insensitive because, among other things, the performers have no true understanding of the social and religious meaning of the dances. Hopis are presumably offended because the dances—however unintentionally—threaten and implicitly show disrespect for Hopi religion by distorting traditional rituals and invoking spiritual powers about which the dancers are themselves completely ignorant. Denunciations from other Pueblo communities are likely to follow. (A recent article on the controversy, published in the Santa Fe New Mexican, includes a short video of the dances.)

Is the case of the Koshare Indian Dancers more or less troubling than the theft of an Inuit design by a commercial fashion house? The latter was done solely for commercial gain, which doesn’t seem to be a factor for performers in the Boy Scout dance troupe. In that sense, the Inuit case is a cruder form of theft. The Boy Scouts apparently mean well, and they insist that their dance expresses appreciation for Native American culture. But their dancing is perceived by Hopi people as hurtful and misguided rather than as admiring. A case can be made that ongoing public performance of the dances constitutes a greater harm to the Hopi, who number around 20,000, than the sale of a handful of overpriced sweaters is to the more numerous Inuit people, although I don’t feel that I’m in a position to say whose hurt might be greater.

Then there’s the recent claim that teaching and practicing yoga by Americans, Canadians, and other people not native to South Asia is a form of cultural appropriation. This made international headlines when a group at the University of Ottawa canceled a yoga course after concluding that teaching yoga in Canada was ethically fraught because the South Asian societies that developed it “have experienced oppression, cultural genocide and diasporas due to colonialism and western supremacy.”

Michelle Goldberg convincingly demolishes this argument in a piece in Slate. She notes that Indian nationalists enthusiastically supported the introduction of yoga in the West to demonstrate the richness and sophistication of Indian culture. The engagement of Indian advocates of yoga with Western audiences changed the discipline significantly. The emerging, cosmopolitan version of yoga has become so identified with India, Goldberg reports, that in 2015 “Narendra Modi, India’s right-wing nationalist prime minister, succeeded in getting the United Nations to recognize International Yoga Day on June 21, which was celebrated with mass yoga demonstrations worldwide.”

The final stop of this tour of widely publicized recent allegations of appropriation is a protest by Oberlin College students who claimed that the apparently inauthentic or substandard ethnic food served in the college’s dining halls was not just unpalatable but represented a form of harmful cultural appropriation. A Japanese student, among others, resented the poor-quality sushi served in Oberlin’s cafeteria. She was quoted as saying, “When you’re cooking a country’s dish for other people, including ones who have never tried the original dish before, you’re also representing the meaning of the dish as well as its culture. So if people not from that heritage take food, modify it and serve it as ‘authentic,’ it is appropriative.”

Most of the published comments that I’ve seen on the Oberlin tempest-on-a-sushi-tray are unsympathetic, even snarky, and justly so. But the students’ denunciation is not just silly. It is a classic case of misusing a moral claim in a way that degrades its meaning and power in much the same way that the casual, uncritical invocation of terms such as “racism” and “ethnocide” distorts their meaning and threatens their legitimacy. When cultures collide, there is bound to be friction and boundary-infringement of many different kinds, some of which may be unjust and destructive, others of which are merely annoying. Still others, of course, evoke delight and mutual appreciation. For a multicultural society to survive and prosper, citizens need to learn to make critical distinctions and exercise judgment about what kind of injuries are worthy of complaint and which are best shrugged off as the price one pays for cultural difference—a price well worth paying.

Additional sources.

The IPinCH project at Simon Fraser University continues to lead the way toward sensible thinking on this topic. Don’t miss their recently posted “final exam” on the difference between cultural appropriation and cultural borrowing.

The Santa Fe New Mexican has just published a comprehensive article by on the circumstances surrounding the 2015 publication of a book documenting Acoma Pueblo’s origin myth by Penguin/Random House, the sale of which is being vigorously contested by Acoma’s traditional authorities.

One thought on “The spectrum of cultural appropriation: Recent cases”