UPRIVER

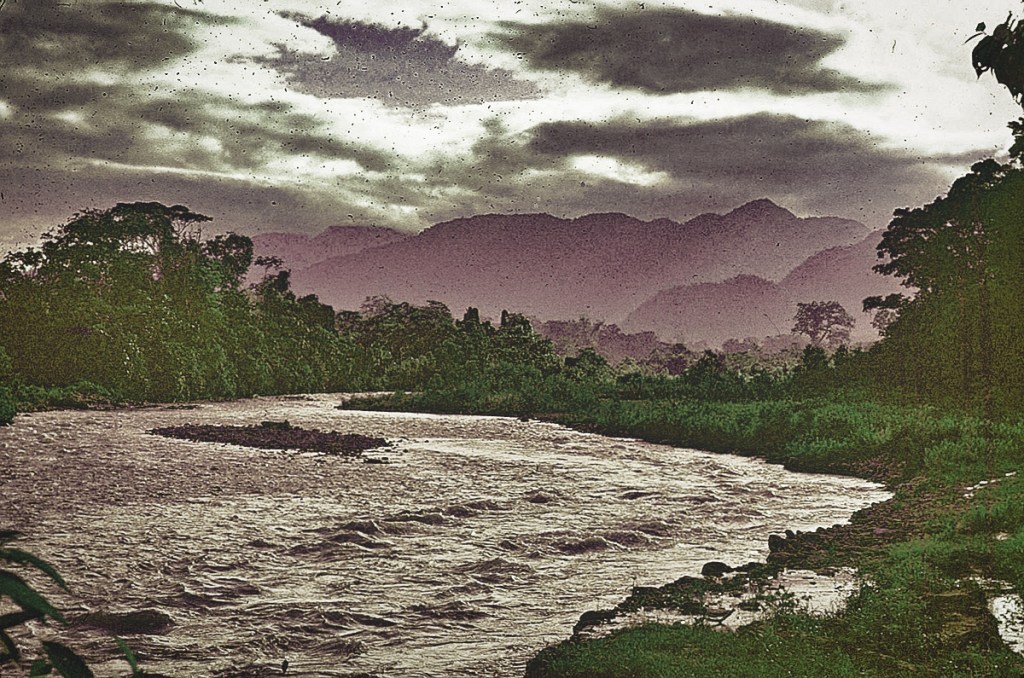

Upriver offers the observations of a working anthropologist and former research-center director. Topics range from the ethics of cultural appropriation to new ways of stewarding Indigenous collections in museums, from the challenges of writing in ways meaningful to the general public to the struggle of Amazonian Native peoples for sovereignty and respect. The Upriver title evokes the challenge of writing against the current of conventional thought.—Michael F. Brown

“All writing is a campaign against cliché. Not just clichés of the pen but clichés of the mind and clichés of the heart.”—Martin Amis

You must be logged in to post a comment.