Francis Spufford’s novel Cahokia Jazz lurked at the edge of my awareness until the New York Times listed it among the best crime novels of 2024 and the holiday season afforded an opportunity to dive into the counter-factual history that undergirds it.

Imagine a United States in which a Mississippian Indigenous nation centered on Cahokia and Monk’s Mound, the largest earthen mound in the pre-contact New World, had somehow not declined in the 1400s and instead remained a vigorous community, albeit one challenged by epidemic disease, Jesuit proselytizing, and the injustices of colonialism. Imagine, too, that the Diné people of the Southwest and the Latter Day Saints in Utah had succeeded in maintaining a high degree of autonomy in polities known, respectively, as Dinetah and the Republic of Deseret. Finally, imagine that Cahokia had been admitted to the Union thanks to the critical role of its fighters in the defeat of the Confederacy in the Civil War. What we know today as St. Louis is a sleepy, insignificant farm village while, on the east side of the Mississippi, Cahokia has developed into a prosperous multi-ethnic city benefitting from the Cahokia people’s ownership of key legs of the transcontinental railroad.

In the 1920s, trouble is brewing in this alternative universe. White capitalists and white-sheeted members of the Ku Klux Klan are plotting to overthrow traditional Cahokia leadership and, among other things, end Cahokia’s collective ownership of land and other resources. A White man is found murdered, his heart ripped from his body. In the minds of the town’s non-Natives, this suggests that some neo-Aztec fanatic, presumably coming from the Indigenous population, is to blame, thus offering pretext for a coup.

Into this situation walks Joe Barrow, police detective and a mixed-race veteran of World War I. The Cahokia police are under tremendous pressure to solve this murder quickly. But in true noir fiction style, Barrow’s investigation is affected by increasingly labyrinthine forces and counterforces driven by racial tension, bootlegging, and mutual incomprehension. (Cahokia people speak and write their own language, Anopa, loosely based on a trade language called the Mobilian Jargon.) Barrow, who is phenotypically Native but brought up in a White-managed orphanage, is torn between his role as detective/cultural outsider and his gifts as a jazz pianist. The latter are lovingly described by the author in a scene where Barrow sits in with his old band and stuns the crowd with his musical dexterity.

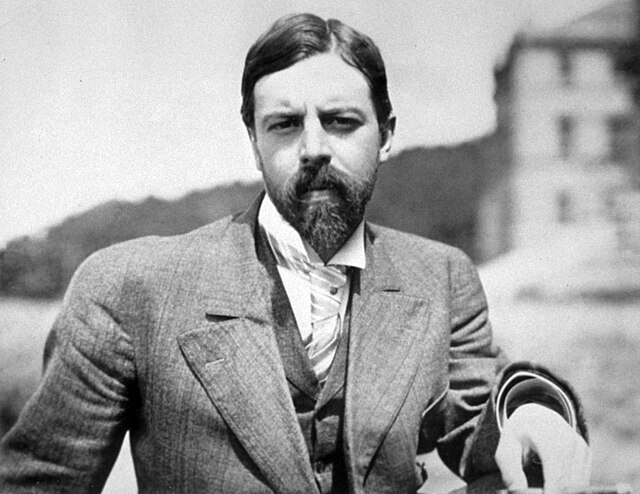

One of the charms of the novel is that Alfred Kroeber appears in a walk-on role as an anthropologist with facility in Anopa as well as at least some knowledge of Cahokia customs. He natters on about matrilineal descent but also serves the narrative by clarifying the history of the community’s embrace of a syncretized version of Roman Catholicism.

Alfred Kroeber, 1920

(Wikimedia, Public domain image)

Francis Spufford, a British writer known primarily for his works of non-fiction before a shift to fiction, is a far better writer than most authors of crime novels. His attention to detail is exceptional, and he generally succeeds in balancing the scene-setting necessary for a counter-factual narrative to remain (fairly) plausible while maintaining the momentum of the story line. There are occasional moments of dialogue that struck me as anachronistic for a book set in the 1920s, but then I’m no expert on how Americans spoke a century ago.

Reviews of Cahokia Jazz have generally been positive. I would have expected a fair amount of pearl-clutching on the order of “How can a White guy from the UK successfully imagine an Indigenous society without falling victim to his own ethnocentrism?” So far, I’ve seen little of that. A long and thoughtful review of the book by Dan Hartland for the website Strange Horizons, flirts with this question, expressing uneasiness. “Again, I don’t write to suggest that Spufford should not write of Indigenous matters,” Hartland says. “I write to suggest he has not done so well.” (For his justification of that judgment, consult the review.)

I would simply respond that Spufford’s book is an entertainment, one that exhibits an admirable imagination while conforming to the conventions of detective fiction, for better or worse. Far from utopian, Cahokian society as portrayed by Spufford has elements that are nearly as troubling as the those of the sinister capitalists who seek to overthrow it. Whatever its limitations as pseudo-ethnography, his novel forces readers to ponder how our nation might have turned out if, for instance, something like 95 percent of the Indigenous population had not been winnowed by epidemic disease and genocidal aggression after contact with Europeans. If that reflection changes the attitude of some readers toward Native Americans and their treatment in a colonial system, can that be a bad thing?

You must be logged in to post a comment.