“How the Ivy League Broke America.” Really?

—November 25, 2024— The December issue of The Atlantic features a cover story by columnist David Brooks arguing, as one can infer from the title, that Ivy League universities should be held responsible for the “populist backlash that is tearing society apart,” among other sins.

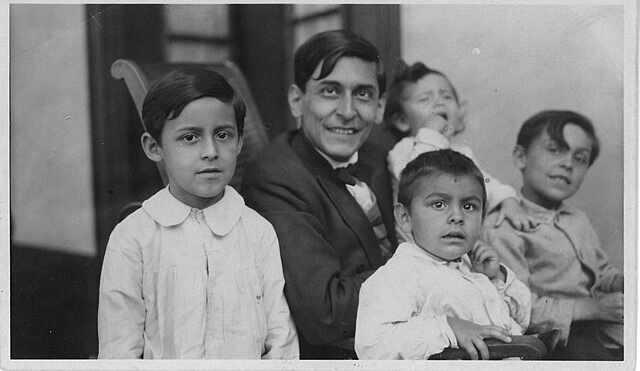

His argument is that the creation of a meritocratic ethic, pioneered by James Conant, the president of Harvard for two decades beginning in 1933, was an attempt to replace a WASP elite defined by breeding and social graces with a cognitive elite based on intelligence, the latter being seen as a more democratic approach than the former. Brooks observes that things haven’t turned out as planned for several reasons. Among them:

(1) Intelligence is overrated.

(2) Being successful in school isn’t the same as being successful in life.

(3) The educational resources of the rich have given their children a significant advantage in intelligence testing and therefore a leg-up in admissions to elite universities.

(4) Meritocratic values have created a caste system that warps the minds and values of students.

(5) Ergo, this system has fostered populist rage.

The solution, says Brooks, is to redirect Ivy League admissions toward finding and admitting young people who show evidence of being “wise, perceptive, curious, caring, resilient, and committed to the common good.” He implies that these character traits can be identified through assessment methods similar to the SAT and ACT, albeit in a less standardized manner. Organizations said to be capable of creating such assessments are starting to emerge, Brooks declares, but his account of their approach is sketchy at best.

Brooks’s analysis is consistent with his post-2024 election op-ed and TV statements that blame populist rage and Trump’s reelection on the arrogance of the college-educated elite, whose occupations, life experiences, and affluence have diminished respect for non-college educated working people

David Brooks is a smart guy, and his assessment of the imperfections of the nation’s elite educational institutions makes valid points. I readily agree that great colleges and universities should value in applicants the admirable qualities that Brooks identifies. That said, it is preposterous to blame eight universities, or even the top twenty universities, for the large-scale economic and cultural pathologies of the last forty years. A degree of rhetorical overreach may be forgivable in a magazine cover story, but as a compelling explanation for our nation’s polarization it is singularly unconvincing.

If you want to know why so many of our fellow citizens are angry, look to decades of industrial outsourcing to the Global South, failure to provide adequate assistance to communities whose economies have been devastated by technological change, and the untrammeled growth of income inequality that now surpasses that of all other developed economies. For good measure, throw in the impact of increasingly fragmented communications media, which profit from alienation and culture-war rage. [Update, 12/5/24. George Packer’s recent article in The Atlantic, “The End of Democratic Delusions,” does as good a job of explaining our present situation as anything I’ve read. Apologies if it’s behind a paywall.]

It’s worth noting that many of the national figures fueling contemporary populism are graduates of Ivy League universities or institutions equally distinguished. Examples: Ted Cruz (Princeton & Harvard). Donald Trump (Penn). Sam Alito (Princeton & Yale). JD Vance (Ohio State & Yale). Clarence Thomas (Holy Cross & Yale). Steve Bannon (Virginia Tech, Georgetown & Harvard). Stephen Miller (Duke). Pete Hegseth (Princeton & Harvard). Christopher Rufo (Georgetown & Harvard). If these universities are little more than leftist indoctrination camps, as some conservatives allege, their record of success is notably weak.

Posted November 25, 2024

Update, December 27, 2024. Michael Roth, the president of Wesleyan University, published this op-ed in the New York Times. Without directly addressing Brooks’s position, Roth offers a more positive view of higher education and how it can rectify some of its problems.

Leave a comment