The repatriation of Indigenous cultural property and human remains has inspired an astonishing volume of academic and popular writing for three decades. Successful repatriations and reburials are celebrated; perceived foot-dragging by repositories prompts withering criticism. Multiple stories by ProPublica document the slow pace of repatriation by some major U.S. institutions and the consternation this produces for many Native Americans.

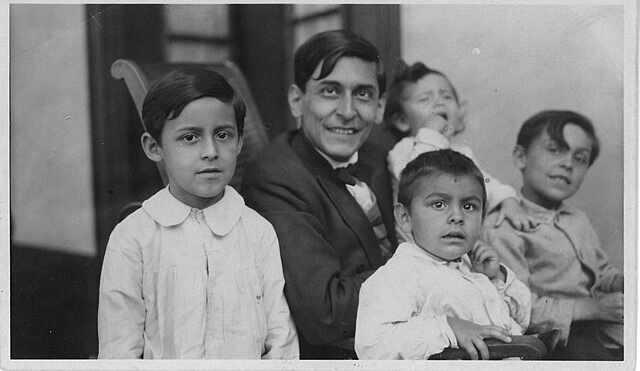

Photo of reburial ceremony at the Presidio of Monterey cemetery, Oct. 2017. Seventeen Native Americans and related funerary objects were laid to rest. The event involved two years of coordination between the U.S. Army, five federally-recognized tribal governments, and one state-recognized tribe. [Public domain image, Wikimedia Commons.]

Far less publicized are repatriation’s frequent complexities and dilemmas, especially involving the reburial of Indigenous ancestors. These dilemmas receive little attention because they often resist concise explanation in short news articles. And some require access to sensitive internal deliberations that Indigenous communities feel should remain closed to outsiders.

An example discussed in an article I co-authored with Margaret Bruchac some years ago concerns the decision of a Pueblo community not to repatriate and rebury certain human remains because traditional burial ceremonies require knowledge of the clan affiliation of the deceased, information typically unavailable when human remains are repatriated. In some parts of the United States, a majority of tribal members may be observant Christians whose community no longer includes a ritual specialist who can lead a burial ceremony appropriate for individuals who died long before Christian missionaries arrived in North America. To my knowledge, little has been written about such dilemmas and the kinds of conversations they provoke within communities, keeping in mind that reburial may be regarded as qualitatively different from the interment of known individuals. Given the creativity and resilience of Indigenous societies, I’m confident that appropriate responses will emerge, although they may require extensive, time-consuming deliberations.

More difficult problems arise when there are conflicting claims to human remains. NAGPRA (the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, 1990) applies only to lineal descendants and federally recognized Indian Tribes, Native Hawaiians and Alaska Natives. Scores of unrecognized or state-recognized tribes are obliged to partner with federally recognized tribes to receive repatriated remains and cultural property. Sometimes these collaborations are cordial and successful; sometimes they aren’t. An additional problem is that state-recognized tribes may lack land suitable for reburial. A journalistic account of these problems in the southeastern U.S. can be accessed here.

A recent WBUR Public Radio story notes the allegedly sluggish efforts by Brown University’s Haffenreffer Museum to repatriate the human remains in its collections. Below the article’s opening paragraphs, however, is a description of a situation that slowed repatriation despite Brown University’s best intentions. To achieve reburial of a person believed to be Wampanoag, “it took 21 years of work . . . [because] several tribes in the area had to agree on the details of the burial and apply for permits to reinter the remains in Warren, Rhode Island.” (Although I have no personal knowledge of the supposedly slow pace of the Haffenreffer’s repatriation of human remains, based on my recent visit to Brown and my conversations with the museum’s staff, I can hardly think of another university museum more committed to fostering equitable relationships with the Indigenous communities represented in its collections.)

As Laura Peers, Lotten Gustafsson Reinius, and Jennifer Shannon note in their introduction to a special section of the journal Museum Worlds, both parties in repatriation events—institutions and Native communities—are compelled to enact rituals consistent with their values and cultural rules. In the institutional case, these typically include documentation, certification, and legal compliance. This encounter between two different value systems can be frustrating to all concerned, especially given power imbalances. Yet one must ask: If the goal is to return the Indigenous dead to their proper place—to “put them to rest,” as the saying goes—shouldn’t great care be taken to ensure that they are reburied in an appropriate manner and suitable location? Such complexities cannot excuse the egregious delays in repatriation associated with some institutions, but they do suggest that critics should bring greater nuance to their complaints.

NAGPRA has forced significant changes in the ways institutions handle Indigenous grave goods and human remains. Collaboration with Indigenous communities is increasingly the only practical and ethical way forward for American archaeologists. Not every community embraces such collaboration—the vexed history of American archaeology with respect to Indigenous peoples is not easily forgotten—but encouraging partnerships are beginning to emerge, as noted in a recent article in Sapiens, the online anthropology magazine. These collaborations build upon relations of mutual respect to find ways of studying human remains and then returning them for reburial subject to a given community’s preferences.

Most journalists’ accounts of repatriation convey the impression that Indian tribes universally demand that their cultural items and sacred objects be returned immediately. People actually involved in repatriation cases know that the situation is far more complex. Many tribes lack a tribal museum or secure storage facility that can house objects of such importance. There may be internal tribal disagreements about who is most qualified to steward returned collections. It is now recognized that a troubling number of objects long in the care of museums—especially textiles and wooden items such as masks—are contaminated by toxic chemicals once used to prevent insect damage, meaning that they cannot be handled without suitable precautions. Communities may therefore be satisfied to have their ownership status confirmed while the objects remain in the care of a repository until such time as a tribe is ready to bring them home.

A prominent example is the Chief White Antelope Blanket, now stewarded by SAR’s Indian Arts Research Center with the full support of the Cheyenne and Arapaho descendants of the blanket’s original owner. The blanket can be seen or displayed only with the descendant group’s permission. At SAR’s expense, the blanket is transported to Oklahoma every two years to be seen by community members. Of course, this kind of arrangement only succeeds if communities are confident that sacred items in a repository’s care are treated respectfully, with full attention to Native preferences. Many museums are working hard to earn the trust necessary for this to work. Given the troubled history of museums and Indian tribes, however, it takes time.

These and other cases cases of careful, time-consuming negotiations serve as a reminder that the historical circumstances and cultural values of Native American communities are highly variable. One-size-fits-all models of repatriation are good for fueling heated rhetoric, but they do a disservice to the diverse histories and traditions of the nation’s hundreds of Native communities.

Leave a comment